Technology in the Law ClassroomTechnology Law / Cyber Law

Submarine Optical Fiber Cables and the Submerged Threats to Data Security in India

Background

In August 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the much-anticipated INR 1,224-crore Chennai-Andaman & Nicobar (A&N) Undersea Internet Cable Network connected via Submarine Optical Fibre Cables (OFCs). The 2,313 km submarine cord was laid between Chennai and Port Blair and would encompass seven archipelagos of the A&N Islands, Port Blair, Swaraj Dweep (Havlock), Long Island, Rangat, Little Andaman, Kamorta, Car Nicobar, and Greater Nicobar. It was said that the submarine cables will assist A&N by making connectivity cheaper and more efficient and by allowing the residents to enjoy the benefits of Digital India, particularly by improving online schooling, telehealth, financial services, online trading, and tourism. This will include up to 400 Gb/s of Broadband bandwidth for Port Blair and 200 Gb/s for other islands.

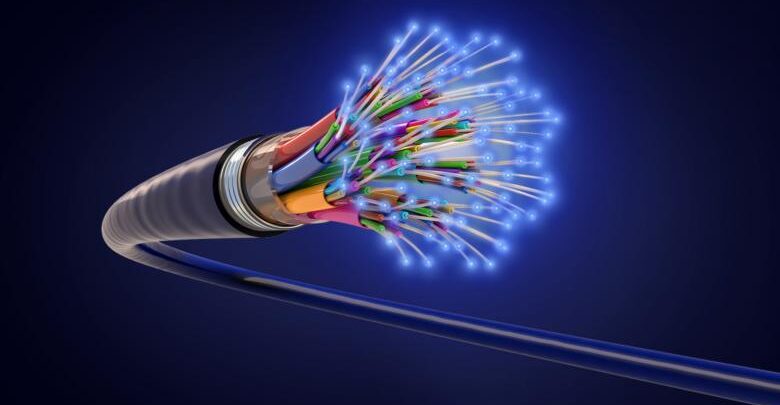

There has been much discourse over the advantages of having such a setup, however, the reliability of the physical infrastructure that forms the basis of the virtual network, that is the security of such submarine fiber-optic networks, is a conspicuous exclusion from this discourse. “ Concealed from normal vision, these submarine transmission cables form a massive network on the seabed, are often no larger than a garden hose, and relay enormous volumes of data across seas.”Despite their role as a vital infrastructure for connectivity, cable networks remain exposed to several evolving cybersecurity threats. This article aims to explore the possible cybersecurity threats posed by Submarine optical fiber cables and to set out recommendations to enhance the security for future projects.

Cyberattacks and Cyber-espionage: Plausible Data security hazards

There seems to be no established definition of the term “cyber-attack,” often used synonymously with “cyber-warfare and cyber-crime”. A cyber-attack in the said case would constitute “a deliberate attack on cable systems laid on the seabed, on cable landing sites, and network security systems”.

Does international law apply to cyberattacks or not, and whether it provides an effective framework for the protection of submarine cables, is a question that’s bound to come to the reader’s mind. Experts and academics in the field have disagreed with what corresponds to cyberattacks under international law. For instance, since its establishment in 2004, the Governmental Group of Experts for the United Nations (GGE) has been discussing whether international law extends to the area of information and telecommunications technology, in the light of International Security.[1] There has also been a controversy as to whether the laws of war, including “jus ad bellum” and “jus in bello” would apply in case of cyberattacks.[2] Despite all the efforts taken in this direction, ambiguity persists to date, resulting in the inexistence of a clear-cut resolution concerning cyberattacks. In addition to the laws of war, international telecommunication legislation also covers cyberattacks (including malicious disruption to cable networks).

International Telecommunications Union (ITU), an agency of the United Nations, has also notified a few rules and guidelines that could extend to cyber-attacks utilising “electromagnetic spectrum” or international telecommunications networks, but none of these specifically deal with the safety of cable networks from malicious attack, making it a cause for concern,

Further, it is also possible to use undersea cables as instruments of “cyber-espionage” and gathering of intelligence. The startling disclosure of Edward Snowden that the United States and the United Kingdom had participated in the “largest programme of suspicion-less surveillance in human history by tapping directly into the Internet backbone,” had made this problem the center of public discourse.

There seem to be 2 methods in which submarine cables can be used to amass intelligence:

- firstly “by placing a recording device on undersea cables” (underwater surveillance); and,

- secondly, by “tapping undersea cables” to gather the data that passes through them.

The “Office of Naval Research” funded the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (“AT&T”) in the late 1950s to build an undersea surveillance system to identify and examine Soviet submarines by “setting up multiple listening posts at strategic chokepoints, arrays of hydrophones strung along cable lengths.” The Navy could therefore intercept the routes of these otherwise deep-diving Soviet subs and monitor them.

Issues with the current International Legal Framework for Cybersecurity Threats

When it comes to cable tapping, whether it is possible to use the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (“UNCLOS”) to deal with “blanket surveillance through the tapping of undersea cables” is not clear. Articles 19 and 20of UNCLOS “regulate the activities of intelligence gathering”, however, it could be said that it only applies to the “intelligence gathering activities that take place inside the maritime domain” and will not regulate the intercepts of submarine cable landing bases. Furthermore, if it is indeed possible to carry out mass surveillance by “physically tapping undersea cables through cable splicing” or otherwise, it is also not certain if UNCLOS is the relevant convention governing such activities.

Although it is plausible for states to conclude a treaty to govern intelligence collection in general, despite the broad difference of views on its legality, it is undoubtedly a far-off prospect. Academics have made proposals on what an international legal framework might look like, and these provide incredibly valuable grounds for a discussion on this subject. However, a larger question has to be raised, irrespective of whether international law would offer a solution. Should submarine cables be used at all for information collection activities? and How could we make these cables that carry volumes of critical information, secure? Protecting cables that run thousands of miles across the deep ocean floor is exceedingly difficult and potentially costly, but there are three major solutions to increase security. Firstly, International law provides inadequate protection for submarine cables, which might be rectified by a new international treaty that includes severe repercussions against any nation found to have interfered with cables. This would at the very least serve to raise the risk threshold for those considering such action.

Secondly, Cables could be installed with sensors that detect the sonar frequencies used by submersibles looking to cause disruption and consequently inform authorities on the ground. Thirdly, Cable Protection Zones could potentially be included in shallower water locations, and surface ships performing “research activity,” fishing, ships anchoring, and diving would all be prohibited in the areas covered by these restrictions.

The Way Forward

Firstly, responsibility for fixing undersea infrastructure should be undertaken by the government. Cable replacements are currently perceived to be a commercial liability, rather than a national security issue. One step in minimising the reaction time to a disturbance or an invasion is to identify cable fixes as national security issues and create a public-private operating strategy, which involves an allocation of resources, to fix them.

Secondly, Telecommunications companies need to provide cable networks with improved protection against future threats. Companies such as “Google, Microsoft, Facebook” etc. either control or lease the undersea bandwidth of almost half the planet. Companies might start by securing cable landing stations while investing in technology for detecting and resisting undersea espionage. States, as well as individuals and organisations, should press for greater protection for undersea networks under international law, including the criminalisation of submarine cable attacks and a stronger framework under UNCLOS.

Thirdly, About the issue specific to India, highlighted initially in the article, apart from the measures to enhance the security of the optical fiber cables, “The National Cyber Security Strategy” would be the most anticipated development. India will need to begin working on a dedicated national cybersecurity law very soon. The need for such a law is crucial because “it would be a critical tool for safeguarding India’s cybersecurity and cyber sovereign interests”.

India is far behind the curve at a time when many other nations have already begun enacting dedicated cybersecurity legislation. According to a recent UNCTAD report, 128 of the 193 member countries of the UN had enacted legislation to provide data protection and privacy. For instance, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in EU member-countries, Protection of Personal Information Act in South Africa, Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) in Canada, and Brazil’s Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados (LGPD).

This is all the more important because India is frequently mentioned as a potential target for cybercriminals and security breaches. Given the lack of cybersecurity law in India, this initiative should be viewed as a stopgap measure before the country adopts a full-fledged cybersecurity law. The govt. had announced in 2020 that as India becomes more digital, and its reliance on cyberspace grows, the country will soon have a new cybersecurity policy. But there haven’t been any significant updates in that regard, which is again an issue that needs to be taken up.

Undeniably, data is the most significant strategic commodity to appear in the 21st century. For national progress and security, access to data and the right to protect its integrity are crucial. There are about 380 undersea cables in use across the world, with a total length of more than 1.2 million kilometers (745,645 miles). Underwater cables are the hidden force that propels the contemporary internet, with many of them being financed in recent years by internet behemoths like Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon. The consequences of sabotaging an underwater cable are that users will be unable to transmit and receive data over it, it could lead to massive data privacy issues, and depending on the cable’s resilience, a region may be shut off from internet access. In terms of operations, this is comparable to breaking a road or rail bridge and denying or channeling traffic through a certain location.

As 5G and artificial intelligence transform our economies into fully interconnected networks, it will become increasingly important to secure data and to take steps forward, in that direction. As submarine cables grow more important to global infrastructure, we observe that the present mechanism regulating it has been neglected, necessitating increased interstate collaboration as well as a revision of the rules governing cable protection. Submarine cable landing points have been identified as some of the network’s most significant nodes since they function as points of access to the global communications and economic domains. A lack of diversity in cable routes is also a significant weakness of the present underwater cable network. In order to build a stronger undersea cable regime, it’d become important to secure cable landing sites from espionage and cybersecurity threats and to ensure that cables aren’t choked at one landing site so that the data does not get concentrated in specific sites. Most importantly, India’s policymakers need to see the safeguarding of undersea cables as a critical national security priority, noting that the cables’ existing legal status is unsettled.

Citation:

Hriti Parekh, Submarine Optical Fiber Cables and the Submerged Threats to Data Security in India, Metacept-Communicating the Law, accessible at https://metacept.com/submarine-optical-fiber-cables-and-the-submerged-threats-to-data-security-in-india

Resources:

[1] Rept. of Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security, at 8, para. 19, U.N. Doc. A/68/98 (June 24, 2013)

[2] U.N. Secretary-General, Developments In the Field of Information and Telecommunications In the Context of International Security, U.N. Doc. A/66/152, at 35-37 (July 11, 2011).